Structure Cannot Be Called Religious Place In Absence Of Proof Of Dedication/User/Grant - Supreme Court

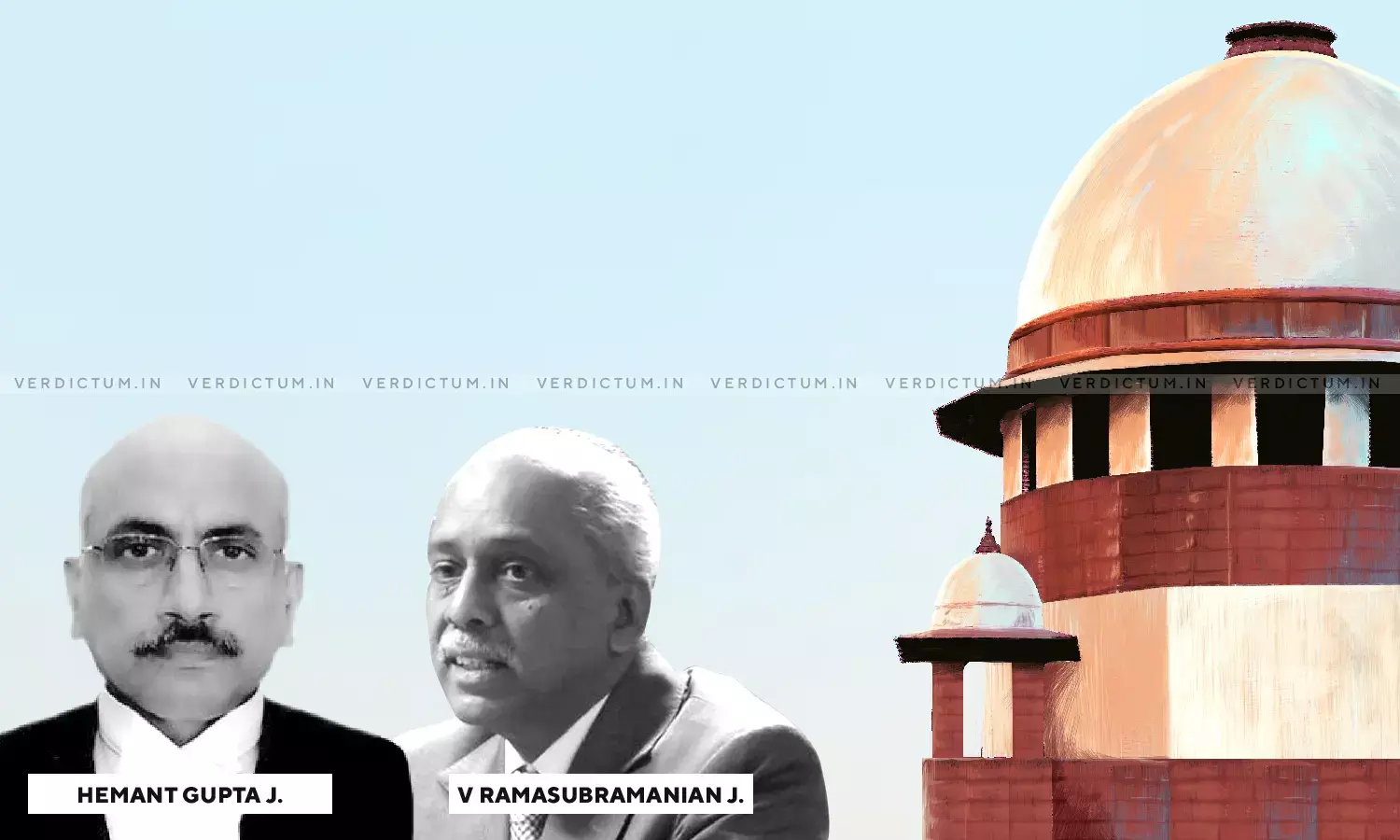

A Supreme Court Bench of Justice Hemant Gupta and Justice V. Ramasubramanian dismissed an appeal against an order of the Rajasthan High Court regarding mining rights in a place which the Waqf Board claimed was a religious place.

The Bench while dismissing the appeal held -

"The report of the experts is relevant only to the extent that the structure has no archaeological or historical importance. In the absence of any proof of dedication or user, a dilapidated wall or a platform cannot be conferred a status of a religious place for the purpose of offering prayers/Namaaz."

Senior Advocate Dr Manish Singhvi appeared on behalf of the State. Senior Advocate Mr. Ranjit Kumar and Senior Advocate Mr. C.S. Vaidyanathan appeared on behalf of the Company.

In 2010, the Company was granted lease of an area for the purposes of mining. In 1963, the Survey Commissioner, Waqf had conducted a survey and had notified a Mosque as Waqf. In 2012, the Anjuman Committee wrote to the Waqf Board, informing them that a few structures of that Mosque were seen at another location, of which the Company had mining rights, and many moons ago labourers used to offer payers there. The Waqf board responded stating that the remains of the Masjid should be saved from mining. However, the Chairman of the Board suspected that their response was being misinterpreted and instead of safeguarding the interest of the Waqf, the Anjuman Committee were using it for personal gain. An FIR was registered, after which the Company approached the High Court.

The High Court constituted an Expert Committee to determine whether the structure at the plot was a Mosque and whether the Petitioner had executed any illegal mining activity within the area. The Committee's majority opinion reflected that the dilapidated structure was not a mosque, nor did it have any archaeological or historic relevance. Aggrieved, the Waqf Board appealed before the Supreme Court.

The Counsel for the Appellant argued that the Expert Committee had no representative of the Board, and as the decision had to be made by the Waqf Tribunal in terms of Section 83 of the Waqf Act, it could not be decided under Article 226 of the Constitution.

The Counsel appearing on behalf of the State argued that in terms of the lease, the decision as to whether the place is a public ground over which the mining activity can be carried out had to be determined by the State Government and it had determined that mining is not permissible.

The Counsels appearing on behalf of the Company contended that the plot allotted for mining was different from the plot on which the Mosque was situated, and there existed no documents on record to indicate otherwise. The Counsels also produced copies of the documents on the basis of which the Appellant had contended that a Mosque was located on the land and therefore no mining activity could take place. They argued that the claim of the Appellant is wholly untenable since the documents reflected that there was a discrepancy about the area over which the religious structure existed. Further, it was also contended using photographs that the structure was dilapidated that there was nothing to suggest that prayers were offered there. The Counsels also argued that that the Tehsildar had given an extensive report of each of the structures existing on the leased land, and lands for graveyards and other religious structures were not included in the lease. To that end, it was contended that the act of identification carried out years before raising of the dispute done by the revenue officials in the course of their official duties carry presumption of correctness, which reflects that the structure carried no religious value.

The Supreme Court opined that there was no document to suggest that the land on which the Mosque was situated was the same as the land allotted for mining. '

To that end, the Court opined that "the claim of the appellant is on a different portion of land and not the land leased to the writ petitioner. There is discrepancy in the total area of the Masjid in the two documents, i.e., the extract produced by the appellant from the register and the second survey report. The letter dated 17.4.2012 by the Anjuman Committee is based upon hearsay and is not of any binding value."

Further, the Court also opined that there was no allegation or proof of either of dedication or user or grant which can be termed as a waqf within the meaning of the Act.

It opined that in the absence of any proof of dedication or user, a dilapidated wall or a platform cannot be conferred a status of a religious place for the purpose of offering prayers.

Accordingly, the Court dismissed the appeal.

Click here to read/download the Judgment