Presumption Under Section 118 Of NI Act Would Remain Until The Contrary Is Proved: Supreme Court

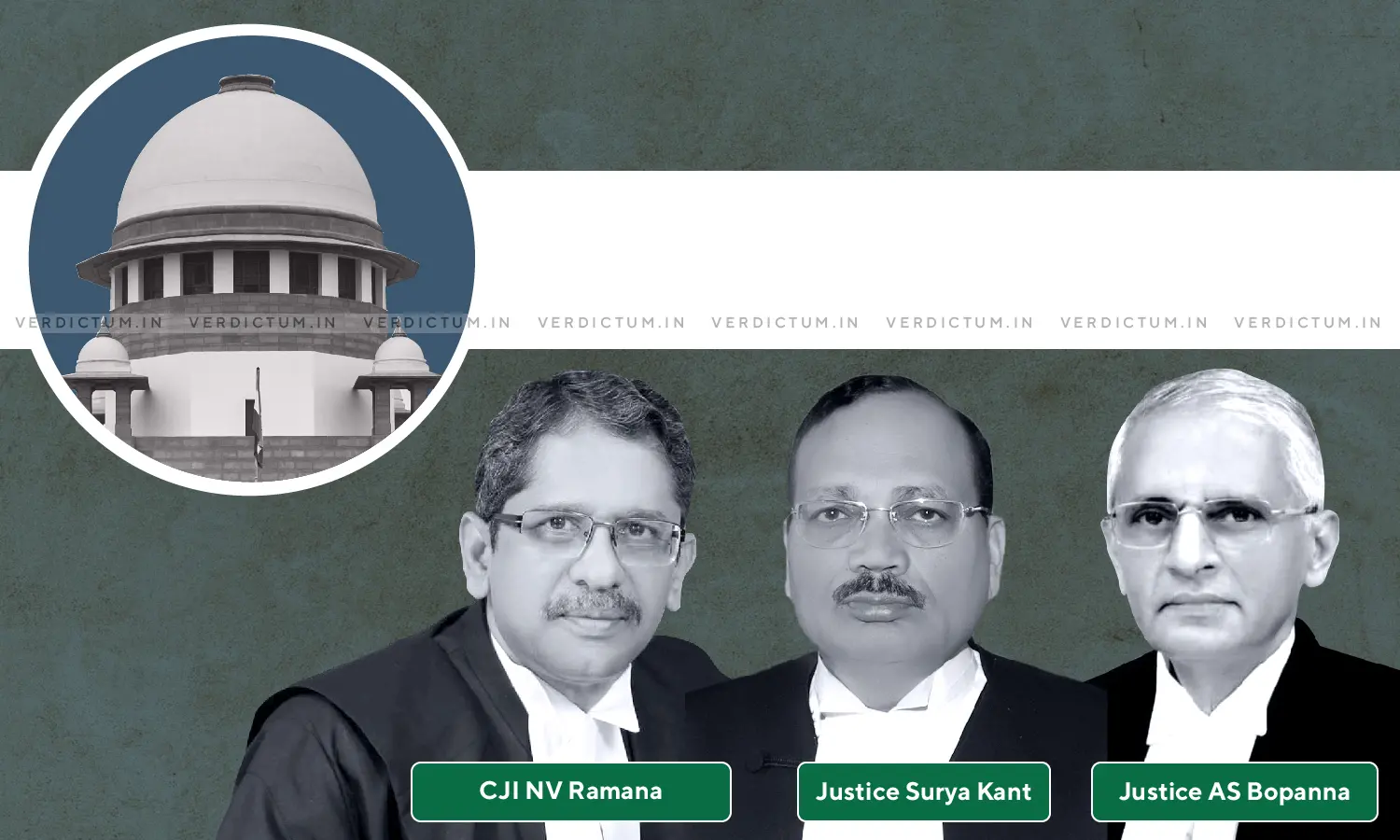

A three-judge Bench comprising of Chief Justice N.V. Ramana, Justice A.S. Bopanna and Justice Surya Kant has held that the gravity of any offence under the Negotiable Instruments Act (N.I Act) cannot be equated with an offence under the Indian Penal Code or other criminal offences while sentencing a convict. The Court has also held that the presumption under Section 118 of the N.I Act will remain until the contrary is proved.

In the case at hand, the Respondent and the Appellant had known each other for few years. The Respondent approached the Appellant and informed that due to his financial difficulty he intended to sell his house. The Appellant agreed to buy the house and negotiated a total sale consideration of Rs. 4,00,000 and after the agreement was executed, the Appellant paid Rs. 3,50,000 to the Respondent as an advance. However, while conducting some inquiries, the Appellant got to know that the house was owned by the Respondent's father and the Respondent had no authority to sell it.

When the Appellant demanded the return of the advance money i.e., Rs. 3,50,000, from the Respondent, the Respondent issued a cheque for the sum of Rs. 1,50,000 as a part of the amount. However, when the Appellant presented the cheque for realization, it came to be dishonoured, with the endorsement 'insufficient funds'. Subsequently, the Appellant issued a notice to the Respondent about the cheque being dishonored and demanded a payment of the cheque amount.

When the Respondent failed to reply to the notice, the Appellant filed a complaint before the Judicial Magistrate of First Class (JMFC), under Section 200 of the Code of Criminal Procedure (CrPC) for prosecuting the Respondent under Section 138 of the N.I Act. Accordingly, the JMFC convicted the Respondent and sentenced him to six months of simple imprisonment and a fine of Rs. 2,00,000.

Aggrieved, the Respondent appealed in the Sessions Court, where the Court confirmed the conviction and dismissed the appeal. Following the dismissal, the Respondent filed a Revision Petition before the Karnataka High Court. The High Court allowed the petition and set aside the conviction passed by the JMFC and confirmed by the Sessions Court, and accordingly, acquitted the Respondent.

In the appeal before the Supreme Court, the Appellant submitted that the Respondent had, in front of the JMFC, admitted to the signature on the agreement, particularly on the cheque. Therefore, the Appellant contended that the "learned JMFC was justified in raising a presumption against the respondent and convicting him since there was no rebuttal evidence or contrary material whatsoever."

The Respondent reiterated his contention that was raised for the first time before the High Court, which the High Court accepted, that the Respondent did not pay the amount but his signature had been secured on the cheque and the agreement under peculiar circumstances. It was contended that the junior to his Advocate in another case was a near relative of the Appellant and thus the Appellant being in a dominant position had obtained the signatures.

While responding to the contentions put forth by the Respondent, the Court asserted, "From the evidence tendered before the JMFC, it is clear that the respondent has not disputed the signature on the cheque. If that be the position, as noted by the courts below a presumption would arise under Section 139 in favour of the appellant who was the holder of the cheque."

The Court also noted, "Insofar as the payment of the amount by the appellant in the context of the cheque having been signed by the respondent, the presumption for passing of the consideration would arise as provided under Section 118(a) of N.I. Act."

The Court referred to Sections 139 and 118(a) of the N.I Act, the Court observed, "The above noted provisions are explicit to the effect that such presumption would remain, until the contrary is proved."

The Court also referred to the following observations made in the Basalingappa vs. Mudibasappa:

1. Once the execution of cheque is admitted, Section 139 of the Act mandates a presumption that the cheque was for the discharge of any debt or other liability.

2. The presumption under Section 139 is a rebuttable presumption and the onus is on the accused to raise the probable defence. The standard of proof for rebutting the presumption is that of preponderance of probabilities.

3. To rebut the presumption, it is open for the accused to rely on evidence led by him or the accused can also rely on the materials submitted by the complainant in order to raise a probable defence. Inference of preponderance of probabilities can be drawn not only from the materials brought on record by the parties but also by reference to the circumstances upon which they rely.

4. That it is not necessary for the accused to come in the witness box in support of his defence, Section 139 imposed an evidentiary burden and not a persuasive burden.

5. It is not necessary for the accused to come in the witness box to support his defence."

"The legal position relating to presumption arising under Section 118 and 139 of N.I. Act on a signature being admitted has been reiterated. Hence, whether there is rebuttal or not would depend on the facts and circumstances of each case.", observed the Court.

The Court further noted that the High Court had referred to certain discrepancies in the agreement relating to the details of the property and the appellant having admitted with regard to not having visited the property or having knowledge of the location of the property. In this regard, the Court observed, "Such consideration, in our opinion, was not germane and was beyond the scope of the nature of litigation. The validity of the agreement in the manner as has been examined by the learned Single Judge may have arisen if the same was raised as an issue and had arisen for consideration in a suit for specific performance of the agreement."

The Court, after considering all the facts, contentions, and evidence, restored the judgment of the JMFC. However, the following question was raised by the Court:

"Whether it is necessary to imprison the respondent at this point in time or limit the sentence to imposition of fine"

The Court accordingly observed, "what cannot also be lost sight of is that more than two and half decades have passed from the date on which the transaction had taken place. During this period there would be a lot of social and economic change in the status of the parties." In this regard, the Court observed "the gravity of complaint under N.I. Act cannot be equated with an offence under the provisions of the Indian Penal Code, 1860 or other criminal offences."

"In that view, in our opinion, in the facts and circumstances of the instant case, if an enhanced fine is imposed it would meet the ends of justice. Only in the event the respondent-accused not taking the benefit of the same to pay the fine but committing default instead, he would invite the penalty of imprisonment. ", held the Court.

The Court upheld the conviction and modified the sentencing by directing the Respondent to pay an enhanced fine of Rs. 2,50,000 to the Appellant within a span of three months, failing which the Respondent would undergo simple imprisonment for six months.