Application U/s. 28A Of Land Acquisition Act Cannot Be Maintained On The Basis Of An Award Passed By Lok Adalat: SC

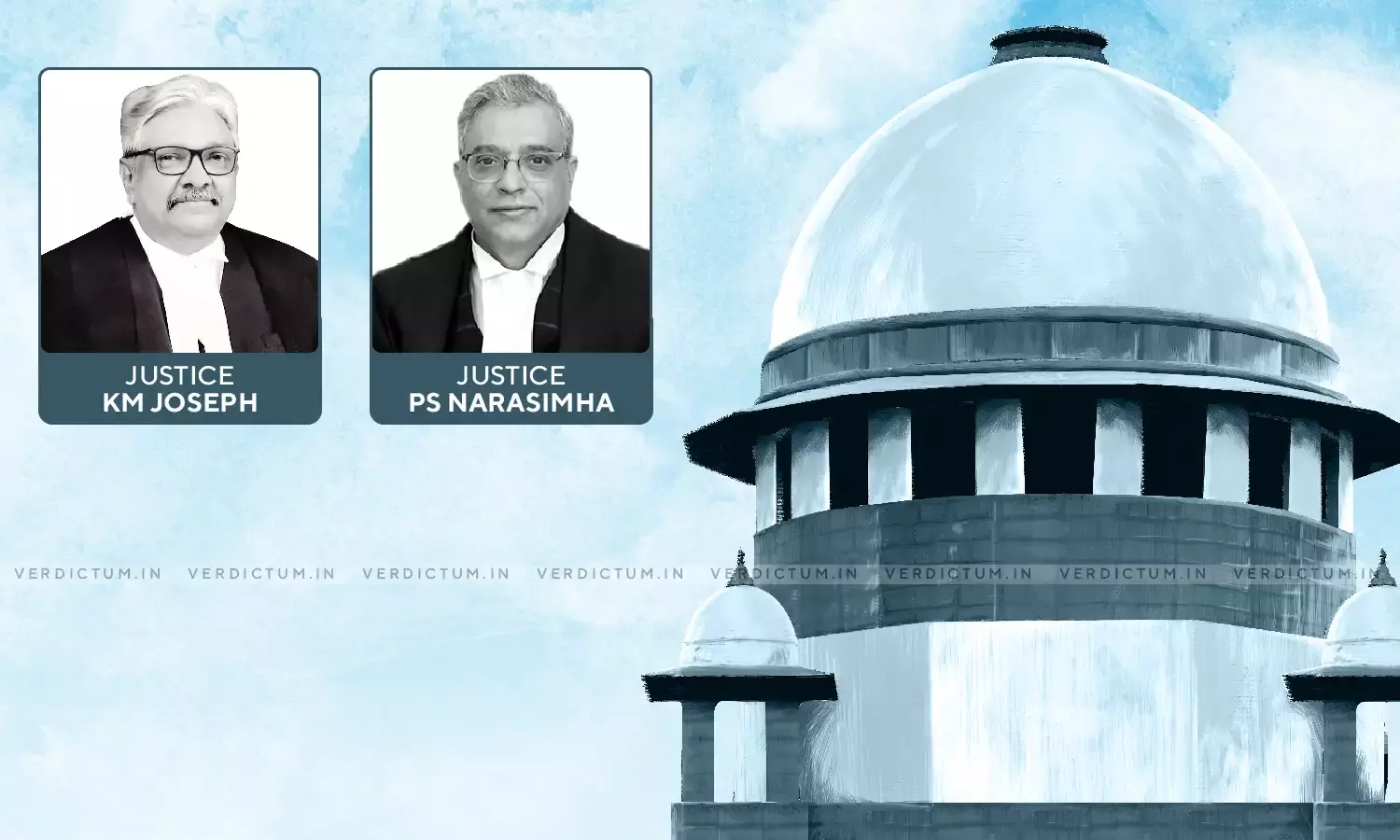

A two-judge bench of the Supreme Court comprising of Justice K.M. Joseph and Justice P.S. Narasimha has held that an application under Section 28A of the Land Acquisition Act, 1894, cannot be maintained on the basis of an award passed by the Lok Adalat under Section 20 of the Legal Services Authorities Act, 1987 Act.

A notification was issued in respect of villages situated in Tehsil Dadri (Situated in District Ghaziabad) for planned industrial development contemplated by the Appellant. By the award of the Land Acquisition Officer, compensation was fixed for the lands belonging to the Respondents herein inter alia at the rate of Rs.24,033 per bigha. The Respondents did not seek enhancement. An application seeking reference was made, which was referred over to a Lok Adalat. The Lok Adalat passed an award compensation was fixed at Rs.297 per square yard as against Rs.20 per square yard which was fixed by the Land Acquisition Officer. This led to the Respondent's filing applications before the Additional District Magistrate who rejected the applications on the basis that the award passed by the Lok Adalat was on the basis of the compromise. This led to the writ petitions being filed by the respondents before the High Court which observed that the award of the Lok Adalat would be deemed to be a decree of the Civil Court and, consequently, the Respondents would be entitled to invoke Section 28A of the Act.

Counsel, Shri Anil Kaushik, appeared for the Appellant, while Senior Counsels, Shri Dhruv Mehta and Shri V. K. Shukla, appeared on behalf of the Respondents

The primary issue in this case was –

Whether the award passed by a Lok Adalat under Section 20 of the Legal Services Authorities Act, 1987 could form the basis for redetermination of compensation as contemplated under Section 28A of the Land Acquisition Act, 1894.

It was contended by the Appellant that Section 28A was not available to be applied when there was no determination by the Court in terms of the Act. It was claimed that Lok Adalats, as constituted under Section 19 of the 1987 Act, have no adjudicatory or judicial function. It was argued that an award of the Lok Adalat merely sets out a compromise reached between the parties and could not be treated as an award by a Court under the Act.

On the other hand, it was contended by the Respondents that an award passed by the Lok Adalat was to be treated as a decree. Thus, being a decree of a Civil Court, the award of the Lok Adalat would provide a firm foundation for similarly circumstanced persons to claim the benefit of Section 28A. Thus, it was submitted that an award passed by the Lok Adalat would satisfy the requirement of an application under Section 28A of the Act.

It was observed by the Court that an award passed by the Lok Adalat under the 1987 Act was the culmination of a non-adjudicatory process. The parties were persuaded by members of the Lok Adalat to arrive at a mutually agreeable compromise. The provisions contained in Section 21 by which the award was treated as if it were a decree intended only to clothe the award with enforceability. The purport of the lawgiver was only to confer it with enforceability in like manner as if it were a decree. Thus, the legal fiction that the Award is to be treated as a decree was limited to the above-mentioned extent.

It was held by the Court that the award passed by the Lok Adalat in itself without anything more was to be treated by the deeming fiction to be a decree. It was not a case where a compromise was arrived at under Order XXIII of the Code of Civil Procedure, 1908, between the parties and the court was expected to look into the compromise and satisfy itself that it was lawful before it assumes efficacy by virtue of Section 21. Thus, the enhancement of the compensation was determined purely on the basis of compromise which was arrived at and not as a result of any decision of a 'Court' as defined in the Act.

It was asserted by the Court, "It may not be legislative intention to treat such an award passed under Section 19 of the 1987 Act to be equivalent to an award of the Court which is defined in the Act as already noted by us and made under Part III of the Act. An award of the Court in Section 28A is also treated as a decree. Such an award becomes executable. It is also appealable. Part III of the Act contains a definite scheme which necessarily involves adjudication by the Court and arriving at the compensation. It is this which can form the basis for any others pressing claim under the same notification by invoking Section 28A. We cannot be entirely oblivious to the prospect of an 'unholy' compromise in a matter of this nature forming the basis for redetermination as a matter of right given under Section 28A."

Thus, the Court held that an application under Section 28A of the Act could not be maintained on the basis of an award passed by the Lok Adalat under Section 20 of the 1987 Act. Hence, the Apex Court allowed the appeal and set aside the impugned judgment of the High Court.

Click here to read/download the Judgment