Daughter Entitled To Inherit Self-Acquired Property Of Father Dying Intestate Under Customary Hindu Law - Supreme Court Reiterates

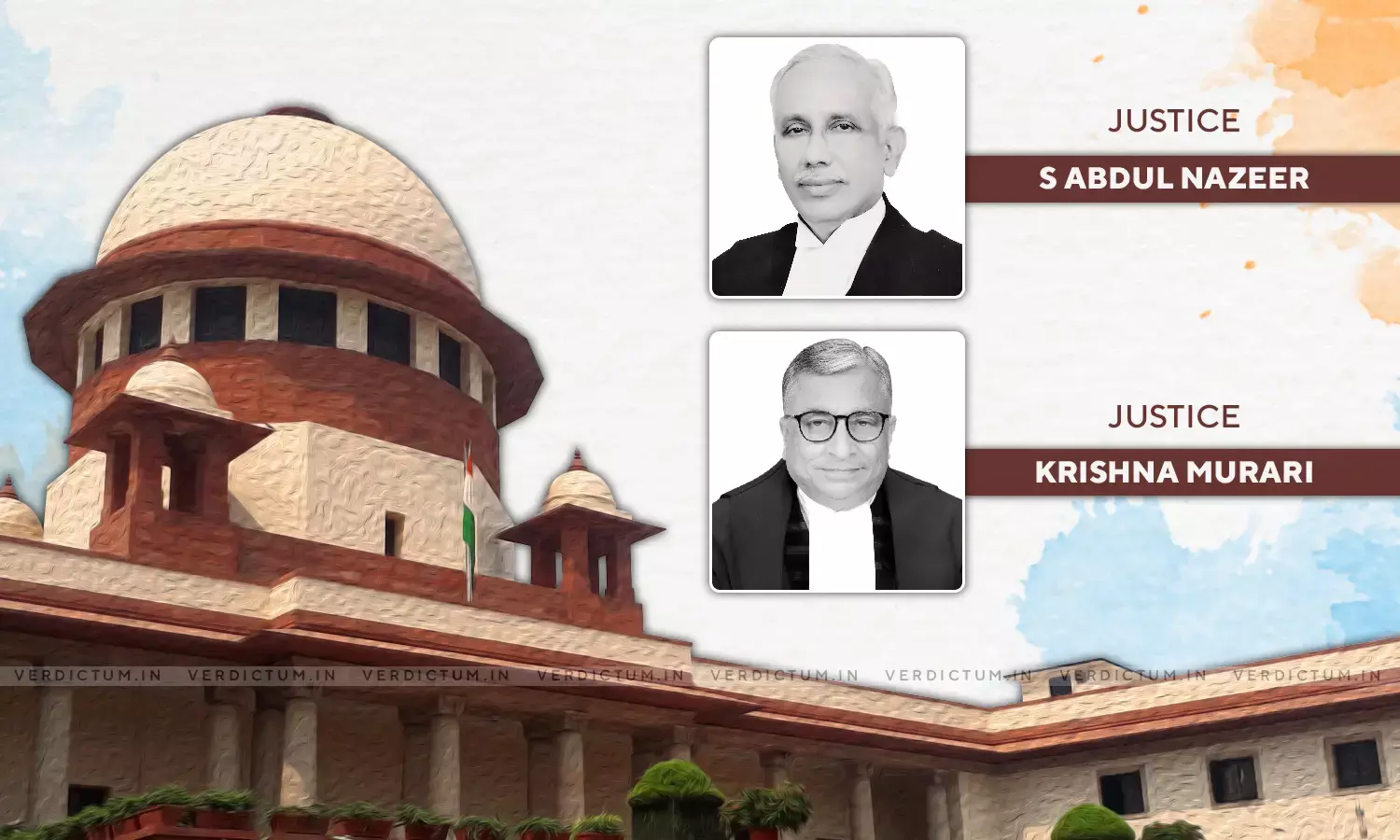

A two-judge Bench of the Supreme Court comprising of Justice S. Abdul Nazeer and Justice Krishna Murari has held that the right of a widow or daughter to inherit the self-acquired property or share in the partition is well-recognized not only under the old customary Hindu law but also by various judicial pronouncements.

Mr. P.V. Yogeswaran appeared on behalf of the appellant while Mr. KK Mani appeared on behalf of the respondents.

In appeal before the Supreme Court was the judgment of the Madras High Court via which the Regular First Appeal of the Appellants was dismissed. Via the RFA, Appellants had challenged the judgment and decree of the Trial Court, which resulted in the dismissal of the original suit.

The suit was filed claiming 1/5th share in the suit properties. The genealogy of the parties finds mention in paragraph 2 of the Judgment.

The suit for partition was filed by one, Thangammal, daughter of Ramasamy Gounder claiming 1.5th share in the suit property on the allegations that the Plaintiff and Defendant nos. 5 and 6, namely, Elayammal and Nallammal and one Ramayeeammal are sisters of Gurunatha Gounder, all the five of them being the children of Ramasamy Gounder.

The Defendants argued that Marappa Gounder died on 15.04.1949 as against 14.04.1957 and hence, Gurnatha Gounder was the sole heir as per the provisions of Hindu Law prevailing prior to 1957, he inherited the suit properties and after his death, the Defendants were continuing as lawful owners.

The property, admittedly, was purchased independently by Marappa. The date of death of Marappa was an issue. The Trial Court came to the conclusion that Marappa died on 15.04.1949 and the suit property would devolve on sole son deceased Ramasamy Gounder, the deceased brother of Marappa Gounder by survivorship and the Plaintiff-Appellant had no right to file the suit for partition and hence, the suit was dismissed.

The findings of the Trial Court were confirmed by the High Court holding that property would devolve upon the Defendant by survivorship.

At the outset, the Supreme Court noted the sources of Hindu Law. On this score, the Court made the following observations:

"The Smritis comprise forensic law or the Dharma Shastra and are believed to be recorded in the very words of Lord Brahma. The Dharma Shastra or forensic Law is to be found primarily in the institutes or collections known as 'Sanhitas', Smritis or in other words, the text books attributed to the learned scholarly sages, such as, Manu, Yajnavalchya, Vishnu, Parasara and Guatama, etc. Their writings are considered by the Hindus as authentic works. On these commentaries, digests and annotations have been written. These ancient sources have thus, charted the development of Hindu Law. These sources constantly evolved over the years, embracing the whole system of law, and are regarded as conclusive authorities. Besides these sources customs, equity, justice, good conscience and judicial decisions have also supplemented the development of Hindu Law."

The Court noted that Mitakshara is supposed to be the leading authority in the school of Benaras. The Court noted that the Mitakshara has always been considered as the main authority for all the schools of law, with the sole exception of that of Bengal, which is mostly covered by another school known as Daya Bhaga. The Court noted that Mitakshara school derives majorly from running commentaries of Smritis written by Yajnavalkya.

The Court noted that the Hindu Law of Inheritance Amendment Act 1929 was the earliest statutory legislation that brought Hindu females into the scheme of inheritance. The Court made the following observations:

"The 1929 Act introduced certain female statutory heirs which were already recognized by the Madras School, i.e., the son's daughter, daughter's daughter, sister and sister's son in the order so specified, without making any modifications in the fundamental concepts underlying the textual Hindu Law relating to inheritance; only difference being that while before the Act, they succeeded as bandhus, under the Act, they inherited as 'gotra sapindas'."

The Court then went on to consider various judicial precedents discussing the law on hand. The following crucial observations were made by the Court.

On a complete reading of the judgment of Privy Council in extenso, the following legal principles are culled out:-

A) That the General Course of descends of separate property according to the Hindu Law is not disputed it is admitted that according to that law such property (separate property) descends to widow in default of male issue.

B) It is upon Respondent therefore to make out that the property herein question which was separately acquired does not descend according to the general Course of Law.

C) According to the more correct opinion where there is undivided residue, it is not subject to ordinary rules of partition of joint property, in other words, if it a general partition any part of the property was left joint the widow of the deceased brother will not participate notwithstanding with separation but such undivided residue will go exclusively to brother.

D) The law of succession follows the nature of property and of the interest in it.

E) The law of partition shows that as to the separately acquired property of one member of a united family, the other members of the family have neither community of interest nor unity of possession.

F) The foundation therefore of a right to take such property by survivorship fails and there are no grounds for postponing the widow's right any superior right of the co-parcenars in the undivided property.

G) The Hindu Law is not only consistence with this principle but is also most consistent with convenience."

The Court, however, noted that there were contradictory opinions about the order of succession to be followed. The Court noted that Section 14 of the Hindu Succession Act 1956 declares the property of a female Hindu to be her absolute property.

The Court noted that "The legislative intent of enacting Section 14(1) of the Act was to remedy the limitation of a Hindu woman who could not claim absolute interest in the properties inherited by her but only had a life interest in the estate so inherited."

The Court, considering Section 15(1)(a) of the 1956 Act made the following crucial observations:

"Thus, if a female Hindu dies intestate without leaving any issue, then the property inherited by her from her father or mother would go to the heirs of her father whereas the property inherited from her husband or father-in-law would go to the heirs of the husband. In case, a female Hindu dies leaving behind her husband or any issue, then Section 15(1)(a) comes into operation and the properties left behind including the properties which she inherited from her parents would devolve simultaneously upon her husband and her issues as provided in Section 15(1)(a) of the Act."

Further, the Bench opined, "The basic aim of the legislature in enacting Section 15(2) is to ensure that inherited property of a female Hindu dying issueless and intestate, goes back to the source."

The Court noted that in the present case since succession opened in 1967 the 1956 Act would apply. The Court noted that the High Court as also the Trial Court did not advert itself to the settled legal propositions. Hence, the judgment of the High Court was set aside.

The suit was decreed and appeal was allowed.