For Preliminary Assessment Of Trying Juvenile As Adult JJB Shall Take Assistance Of Psychologists, Physio-Social Workers - SC

The Supreme Court while interpreting the proviso Section 15(1) of the Juvenile Justice (Care and Protection of Children) Act, 2015 has held that the said proviso is mandatory in nature.

The Court held, "...where the Board is not comprising of a practicing professional with a degree in child psychology or child psychiatry, the expression "may" in the proviso to section 15(1) would operate in mandatory form and the Board would be obliged to take assistance of experienced psychologists or psychosocial workers or other experts."

The Court upheld the order of the Punjab and Haryana High Court in the murder case of a class II student to the extent of remanding the matter-whether the murder-accused should be tried as adult, back to the Juvenile Justice Board (the board) for fresh consideration.

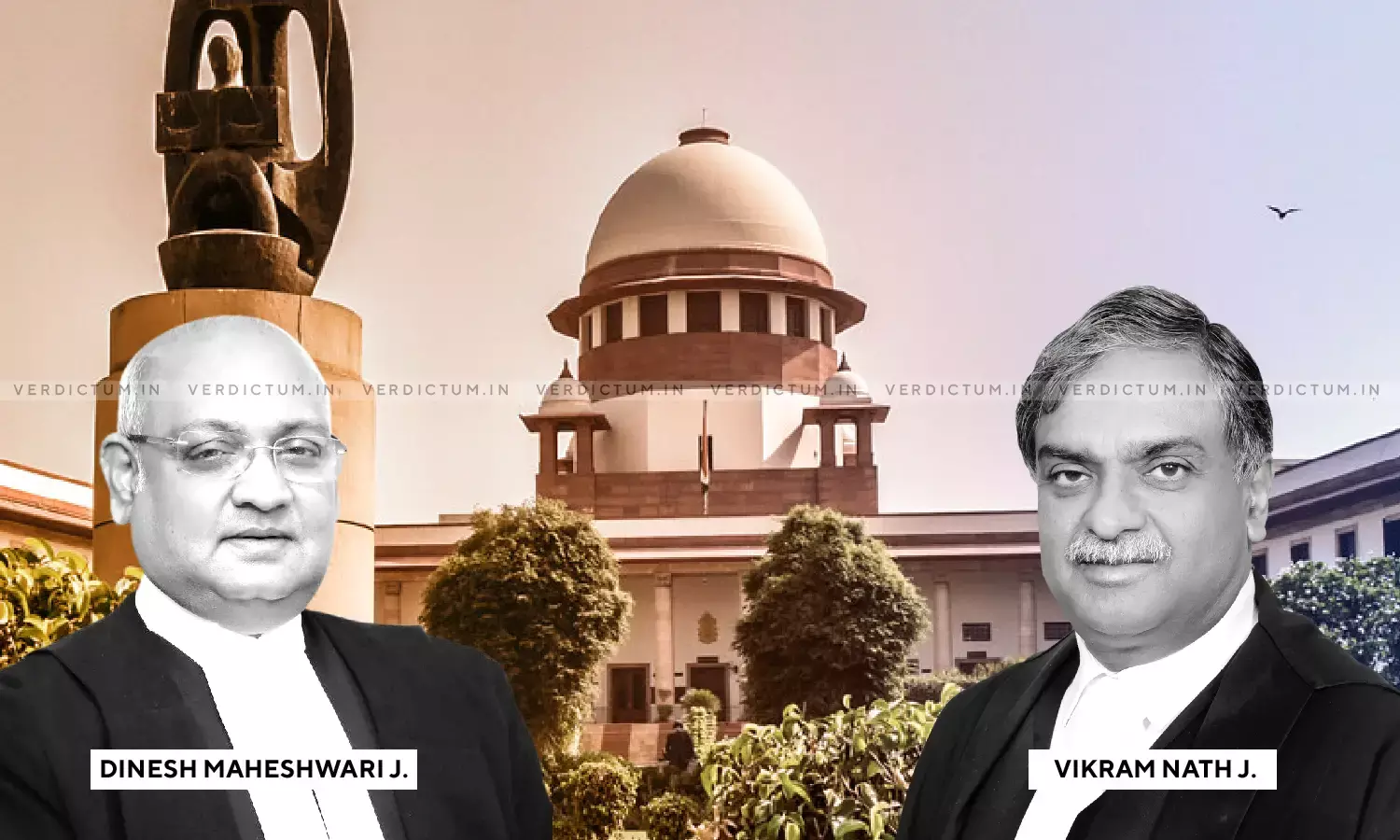

"…we have no hesitation in agreeing wit the ultimate result of the High Court in remanding the matter for a fresh consideration after rectifying the errors on lack of adequate opportunity.", the Bench of Justice Dinesh Maheshwari and Justice Vikram Nath held.

This came after the board had passed an Order holding that there was a need of trial for the murder accused as an adult. However this decision was set aside by the High Court.

However on the HC's direction directing further examination of the child (accused), the Court held "Today, after 3½ years, we are not in a position to give an opinion as to whether any further test can be carried out at this stage as the age of the child is now more than 21 years. However, we leave it to the discretion of the Board or the psychologist who may be consulted as to whether any fresh examination would be of any relevance/assistance or not."

In this case a Class II student of a school was found in the toilet with his throat slit. He was rushed to the hospital but was declared brought dead. After the investigation was transferred to CBI a Class XI student of the same school was arrested. He was aged 16 years as on the relevant date.

Section 15 of the Juvenile Justice (Care and Protection of Children) Act, 2015, mandates that where a child in conflict with law who has committed a heinous offence and is above the age of 16 years, the Board would make a preliminary assessment and pass appropriate orders in accordance with the provisions of subsection (3) of section 18 of the Act, 2015.

In that process, the Board called for a report from the expert psychologist, also interacted with the accused, considered the Social Investigation Report(SIR) as also other material placed before it and proceeded to pass an order holding that there was a need of trial of the accused as an adult.

The Children's Court upheld the decision of the Board and dismissed the appeal. Aggrieved the accused moved High Court whereby the Court allowed the Revision, set aside the orders passed by the Board as also the Children's Court and remanded the matter to the Board for a fresh consideration.

Feeling aggrieved by the decision of the High Court CBI approached Supreme Court.

Additional Solicitor General Vikramjit Banerjee appeared for the CBI-appellant, Advocate Sushil Tekriwal, for the complainant-appellant and Senior Advocate Sidharth Luthra, appeared for the respondent-accused.

Advocate Sushil Tekriwal argued that Children aged 16-18, prosecuted for heinous crimes were assigned a separate class by legislature, therefore, they may be denied the protective cover. He contended that there was no illegality in concurrent findings of the two Courts below and that the High Court had broadened its jurisdiction too far, going into correctness of the medical board report and the correctness of various other factual aspects.

Additional Solicitor General on behalf of the CBI-appellant asserted that the requirement for cross-examination of the psychologist, and supply of the expert's reports to the respondent or his guardians prior to the passing of the preliminary assessment was erroneous.

The CBI attempted to prove its proper conduct by asserting that the accused was treated in a childfriendly manner, and examined in line with the Act, 2015.

On the other hand Senior Advocate Sidharth Luthra reiterated the stand of the Supreme Court that the interests of children should be protected and to treat them as adults is an exception to the rule.

He submitted that the child was kept in police lockup and subsequently a confession was extracted from him. He argued that on the date of the psychological assessment, the respondent was aged 16 years and 7 months. However, the tests administered to him were appropriate for children upto 11 years (CPM) and 15 years (Malins).

He argued that the Board failed to take into account the statement of the respondent that CBI called him inside, beat him up and asked him to speak and erroneously concluded that the respondent had sufficient mental and physical capacity to commit the offence.

At the outset the Court noted the major consequences if the child is tried as an adult. Firstly Court noted that the sentence or the punishment can go up to life imprisonment if the child is tried as an adult, Secondly that where the child is tried as a child by the Board, then he would not suffer any disqualification attached to the conviction of an offence, whereas the said removal of disqualification would not be available to a child who is tried as an adult by the Children's Court.

Therefore the Court held "These consequences are serious in nature and have a lasting effect for the entire life of the child. It is well settled that any order that has serious civil consequences, reasonable opportunity must be afforded."

On perusal of the psychologist's report the Court observed that the report mentioned that it was only for the purpose of assessing the mental capacity of the child and that the report did not mention anything about the child's knowledge of the consequences of committing the alleged offence.

The Court further observed "The Board and the Children's Court apparently were of the view that the mental capacity and the ability to understand the consequences of the offence were one and the same, that is to say that if the child had the mental capacity to commit the offence, then he automatically had the capacity to understand the consequences of the offence. This, in our considered opinion, is a grave error committed by them."

The Court noticed that the Board consists of three members, one is a Judicial Officer First Class and two social workers. The Court noted that the Board's constitution may not necessarily have an expert child psychologist.

The Court held that the power to carry out the preliminary assessment rests with the Board and the Children's Court and that it (Court) cannot delve upon the exercise of preliminary assessment.

The Court left it to the discretion of the Board or the psychologist to decide whether any fresh examination would be of any relevance/assistance or not.

Before parting with the Judgment the Court opined the Central Government and the National Commission for Protection of Child Rights and the State Commission for Protection of Child Rights to consider issuing guidelines or directions which may assist and facilitate the Board in making the preliminary assessment under section 15 of the Juvenile Justice (Care and Protection of Children) Act, 2015.

"We also make it clear that any observations made in our order which may be touching the merits of the case was only for the purpose of deciding these appeals and the same would in no way influence the Board or the Children's Court or the High Court. They may proceed to decide the matters objectively on merits in accordance with law.", the Court held while dismissing the appeal filed by the complainant and CBI.

Click here to read/download the Judgment