Accused Entitled To Benefit Of Doubt If Some Circumstances In Chain Can Be Explained By Any Other Reasonable Hypothesis: Supreme Court

The Supreme Court observed that in a case based only on circumstantial evidence, the accused is entitled to the benefit of the doubt if there is any snap in the chain of circumstances.

The Court allowed a Criminal Appeal filed by the husband of the deceased, contesting a conviction upheld by the High Court.

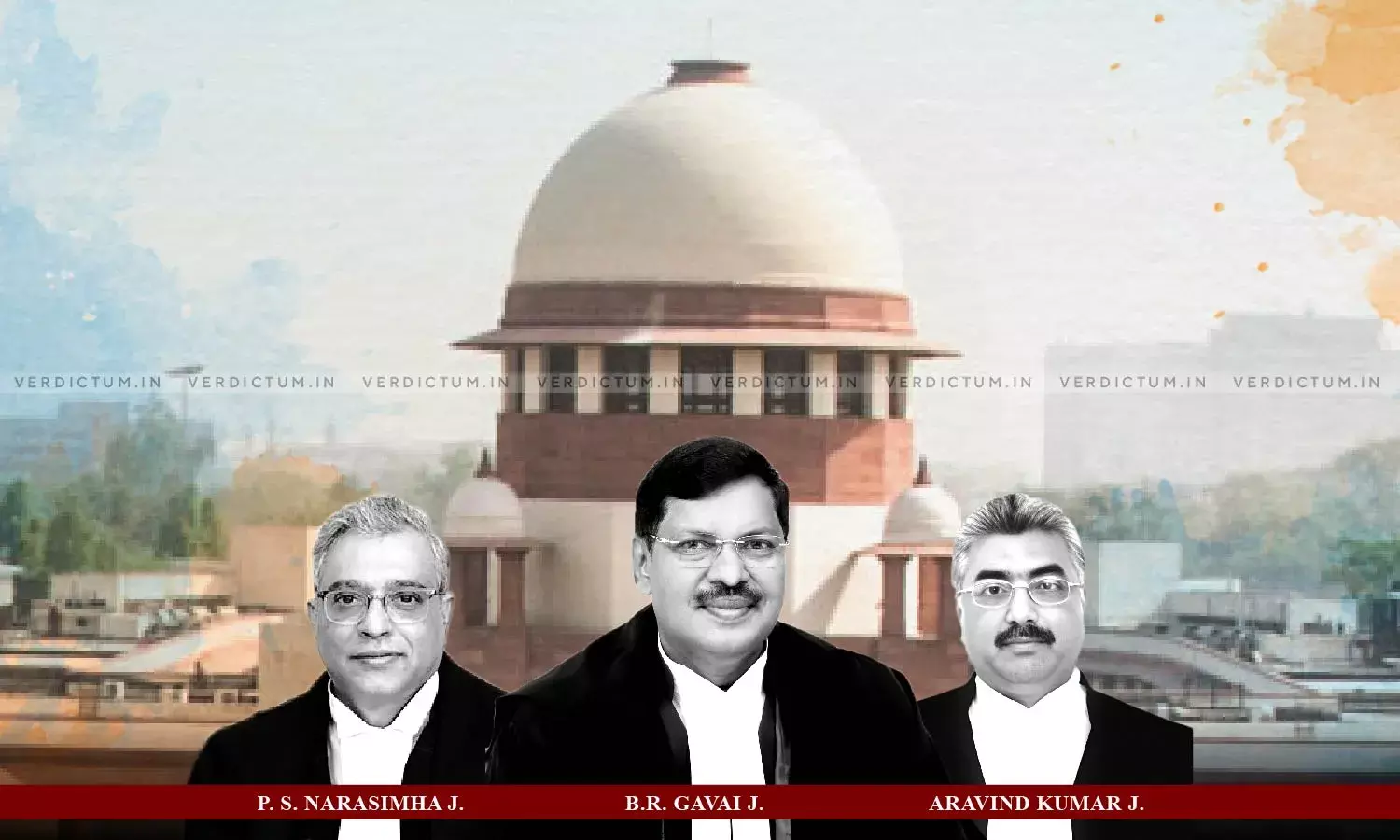

“When the conviction is to be based on circumstantial evidence solely, then there should not be any snap in the chain of circumstances. If there is a snap in the chain, the accused is entitled to benefit of doubt. If some of the circumstances in the chain can be explained by any other reasonable hypothesis, then also the Accused is entitled to the benefit of doubt”, the Bench comprising Justice B. R. Gavai, Justice P. S. Narasimha and Justice Aravind Kumar observed.

Advocate Abhimanyu Tewari appeared for the Appellant and Advocate Prateek Chaddha appeared for the State.

The case involved the Appellant (Second Accused), Accused of causing the death of his wife, along with the Accused. Despite attempts by relatives to end the illicit relationship of the Accused and the Appellant, their relationship persisted. Allegedly, on the night of May 18, 1999, and May 19, 1999, the Appellant with the Accused intentionally administered poison to eliminate the Appellant’s Wife. Both were charged under Sections 302 and 34 of the Indian Penal Code, 1860 (IPC), and the Trial Court convicted and sentenced them to life imprisonment.

A Criminal Appeal was filed challenging the High Court's judgment that upheld the conviction and sentence of the Appellant while acquitting the Accused.

The Trial Court dismissed the suicide theory, considering the absence of injuries insufficient to rule out forceful poisoning. It concluded the prosecution established a case against the Appellant and the Accused. On appeal, the High Court affirmed the Trial Court's findings on the Appellant but acquitted the Accused, citing a lack of evidence proving her presence on the relevant night.

The Court noted that the prosecution's case, lacking an eyewitness, relied on circumstantial evidence, necessitating the establishment of a complete chain of circumstances to prove guilt beyond reasonable doubt. The key motive, an illicit relationship between the Appellant and the Accused, has been substantiated through testimonies. The crucial circumstance was the presence of the Appellant and the Accused in the Appellant's house on the relevant night, triggering Section 106 of the Evidence Act. The proof of presence is linked to the Appellant's opportunity to administer poison, reinforcing the prosecution's case.

The Court, emphasized the consequences when an offence occurs within a house, observing a lower standard of proof and a limited shifting of the onus to the Accused to explain the circumstances leading to death. The Trial Court convicted the Appellant, while the High Court acquitted the Accused, extending the benefit of the doubt.

The Court considered the omission of testimonies and highlighted concerns about the credibility of their evidence. The omissions and improvements, not solely attributable to illiteracy, cast doubt on the established presence of the Accused, underscoring the need for careful evaluation.

The prosecution witness no 5, being a chance witness with a limited side-on view of the Accused persons in a jeep, cannot be solely relied upon to establish their involvement in the alleged crime. The Court questions the established presence of the Accused in the house on the night of the incident, emphasizing that this circumstance has not been convincingly proved.

The Court, however, expressed doubt about the certainty of a homicide, noting that the evidence, even if assuming the presence of the Accused, fails to exclude the possibility of suicide. The Court emphasized the principle that the prosecution must establish the charge beyond a reasonable doubt and acknowledged that the Accused only needs to create doubt. The absence of a specific plea of alibi in the Appellant's statement under Section 313 CrPC was highlighted, emphasizing that such statements are not considered evidence.

The Bench noted that per the prosecution's case, the Appellant and Accused were jointly present in the Appellant's house on the night of May 18, 1999, and were seen leaving together on May 19, 1999, having committed the offence of administering poison to the deceased. While both were tried together, the High Court acquitted the Accused, citing doubts about her presence.

However, the Apex Court noted that the High Court did not extend the same benefit of the doubt to the Appellant, reasoning that, being the husband, his presence in the house was natural. The State has accepted the Accused’s acquittal, and according to the Court, if her presence is doubtful, the same evidence cannot reliably establish the Appellant's presence. The Apex Court noted that the High Court's distinction between the cases of the Appellant and Accused was perverse and unconvincing.

In light of the doubts raised regarding the presence of the Accused with the Appellant, the Apex Court deemed it unnecessary to delve into the consideration of other circumstances presented by the prosecution. The failure to convincingly establish a single circumstance can result in a break in the chain of circumstances.

In cases relying solely on circumstantial evidence, the Bench noted that any gap or the possibility of an alternative reasonable explanation entitles the Accused to the benefit of the doubt.

Accordingly, the Court allowed the Appeal and Set aside the impugned judgment of conviction.

Cause Title: Darshan Singh v State Of Punjab (2024 INSC 19)