Several Inbuilt Safeguards Provided By Parliament While Enacting PMLA - SC While Upholding Constitutional Validity Of Provisions Of PMLA

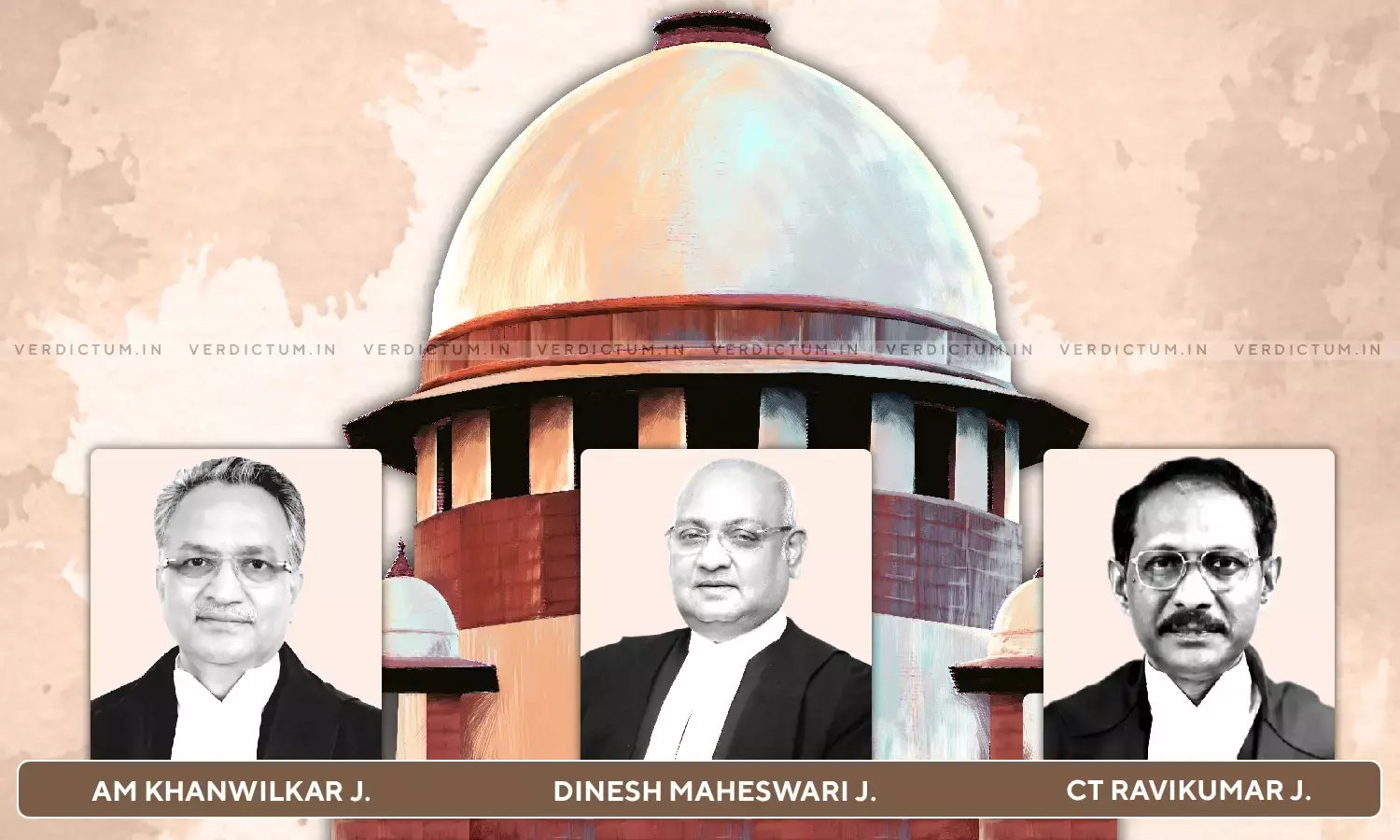

In what would be a path-breaking Judgment for the criminal law jurisprudence in the country, the 3 Judge Bench of the Supreme Court comprising Justice A.M. Khanwilkar, Justice Dinesh Maheshwari and Justice CT Ravikumar has inter alia upheld the constitutional validity of certain provisions of the Prevention of Money Laundering Act, 2002 ["PMLA"] that relate to the power of arrest, attachment and search and seizure conferred on the Enforcement Directorate ["ED"].

Mr. Kapil Sibal, Mr. Sidharth Luthra, Dr. AM Singhvi, Mr. Mukul Rohatgi, Mr. Amit Desai, Mr. Niranjan Reddy, Dr. Menaka Guruswamy, Mr. Aabad Ponda, Mr. Siddharth Aggarwal, Mr. Mahesh Jethmalani, Mr. N Hariharan, Mr. Vikram Chaduari, Senior Advocates and Mr. Abhimanyu Bhandari and Mr. Akshay Nagarajan, Advocates appeared for the private parties. On the other hand, Mr. Tushar Mehta, SG, and Mr. SV Raju, ASG appeared on behalf of the Union of India.

Pertinently, the Supreme Court held that the officers of the ED who investigate money laundering cases under the PMLA would not fall under the definition of the term police officers and as a consequence, the statements that are recorded by the officers under Section 50 of the PMLA would not be hit by Article 20(3) of the Constitution that provides for the right against self-incrimination.

On the PMLA: -

The Court noted that the PMLA was enacted to address the urgent need to have comprehensive legislation inter alia for preventing money-laundering, attachment of proceeds of crime, adjudication and confiscation thereof including vesting of it in the Central Government, setting up of agencies and mechanisms for coordinating measures for combating money-laundering and also to prosecute the persons indulging in the process or activity connected with the proceeds of crime.

The Court held that the expression investigation under the Act must be regarded as interchangeable with the function of inquiry to be undertaken by the authorities for submitting such evidence before the Adjudicating Authority.

The Court made the following crucial observations:

"In other words, merely because the expression used is "investigation" _— _which is similar to the one noted in Section 2(h) of the 1973 Code, it does not limit itself to matter of investigation concerning the offence under the Act and Section 3 in particular. It is a different matter that the material collected during the inquiry by the authorities is utilised to bolster the allegation in the complaint to be filed against the person from whom the property has been recovered, being the proceeds of crime. Further, the expression "investigation" used in the 2002 Act is interchangeable with the function of "inquiry" _to be undertaken by the Authorities under the Act, including collection of evidence for being presented to the Adjudicating Authority for its consideration for confirmation of provisional attachment order. We need to keep in mind that the expanse of the provisions of the 2002 Act is of prevention of money-laundering, attachment of proceeds of crime, adjudication and confiscation thereof, including vesting of it in the Central Government and also setting up of agency and mechanism for coordinating measures for combating money-laundering."

- Section 3 of PMLA

This Section offers the definition of the offence of money laundering. The Supreme Court, in this behalf, made the following crucial observations.

"To put it differently, the section as it stood prior to 2019 had itself incorporated the expression "including", which is indicative of reference made to the different process or activity connected with the proceeds of crime. Thus, the principal provision (as also the Explanation) predicates that if a person is found to be directly or indirectly involved in any process or activity connected with the proceeds of crime must be held guilty of offence of money-laundering. If the interpretation set forth by the petitioners was to be accepted, it would follow that it is only upon projecting or claiming the property in question as untainted property, the offence would be complete. This would undermine the efficacy of the legislative intent behind Section 3 of the Act and also will be in disregard of the view expressed by the FATF in connection with the occurrence of the work "and" preceding the expression "projecting or claiming" therein."

The Court then proceeded to consider whether the offence under Section 3 of the PMLA is a standalone offence?

The Court noted that the authority of the Authorised Officer under the Act to prosecute any person for offence of money laundering would get triggered only when there are proceeds of crime within Section 2(1)(u) of the Act and it is involved in. any process or activity.

The Court held that "In other words, the Authority under the 2002 Act, is to prosecute a person for offence of money-laundering only if it has reason to believe, which is required to be recorded in writing that the person is in possession of "proceeds of crime". Only if that belief is further supported by tangible and credible evidence indicative of involvement of the person concerned in any process or activity connected with the proceeds of crime, action under the Act can be taken forward for attachment and confiscation of proceeds of crime and until vesting thereof in the Central Government, such process initiated would be a standalone process."

- Section 5 of the PMLA:

The Court held that there are several inbuilt safeguards provided for by the Parliament while enacting the PMLA. The Court noted that "We find force in the stand taken by the Union of India that the objectives of enacting the 2002 Act was the attachment and confiscation of proceeds of crime which is the quintessence so as to combat the evil of money-laundering. The second proviso, therefore, addresses the broad objectives of the 2002 Act to reach the proceeds of crime in whosoever's name they are kept or by whosoever they are held."

- Section 8 of the PMLA:

Importantly, this Section deals with attachment, adjudication, and confiscation.

The Court noted that PMLA is a special self-contained law. The Court also noted that Section 17 provides for inbuilt safeguards.

On Rule 3(2) the Court made the following observations:

"In the first place, it is unfathomable that the effect of amending Act is being questioned on the basis of unamended Rule. It is well-settled that if the Rule is not consistent with the provisions of the Act, the amended provisions in the Act must prevail. The statute cannot be declared ultra vires on the basis of Rule framed under the statute. The precondition in the proviso in Rule 3(2) cannot be read into Section 17 of the 2002 Act, more so contrary to the legislative intent in deleting the proviso in Section 17(1) of the 2002 Act. In any case, it is open to the Central Government to take necessary corrective steps to obviate confusion caused on account of the subject proviso, if any."

- Search of Persons:

This concerns Section 18 of the Act. On this point, the Court made the following pertinent observations:

"Suffice it to observe that the provision in the form of Section 18, as amended, is a special provision and is certainly not arbitrary much less manifestly arbitrary. Instead, we hold that the amended provision in Section 18 has reasonable nexus with the purposes and objects sought to be achieved by the 2002 Act of prevention of money-laundering and attachment and confiscation of property (proceeds of crime) involved in money-laundering, as also prosecution against the person concerned for offence of money-laundering under Section 3 of the 2002 Act."

- On Section 19 - Arrest

The Court noted that it had no hesitation in upholding the validity of this Section and held that this provision has reasonable nexus with the purposes and objects sought to be achieved by the Act of prevention of money-laundering and confiscation of proceeds of crime involved in money-laundering including to prosecute persons involved in the process or activity connected with the proceeds of crime so as to ensure that the proceeds of crime are not dealt with in any manner which may result in frustrating any proceedings relating to confiscation thereof.

- Bail

This was the most contested area before the Court. The principal grievance was about the twin conditions specified in Section 45 for bail.

The Court made the following crucial observations:

"Thus, it is well settled by the various decisions of this Court and policy of the State as also the view of international community that the offence of money-laundering is committed by an individual with a deliberate design with the motive to enhance his gains, disregarding the interests of nation and society as a whole and which by no stretch of imagination can be termed as offence of trivial nature. Thus, it is in the interest of the State that law enforcement agencies should be provided with a proportionate effective mechanism so as to deal with these types of offences as the wealth of the nation is to be safeguarded from these dreaded criminals. As discussed above, the conspiracy of money-laundering, which is a three-staged process, is hatched in secrecy and executed in darkness, thus, it becomes imperative for the State to frame such a stringent law, which not only punishes the offender proportionately, but also helps in preventing the offence and creating a deterrent effect."

The Court held that the provision in form of Section 45 after the 2018 amendment was reasonable and has direct nexus with the object and purposes sought to be achieved. As such, the Court held that it did not suffer from the vice of arbitrariness or unreasonable.

Having said that, the Supreme Court noted that the question as to whether some of the amendments to the PMLA could not have been enacted by the Parliament by way of a Finance Act was not examined via the instant judgment and that the same was left open for being examined along with or after the decision of the Larger Bench comprising 7 Judges in the Rojer Mathew Case.

Accordingly, the bunch of SLPs were disposed of and others were detagged.

Click here to read/download the Judgment