NI Act – Partner Of Firm Cannot Be Convicted Unless Firm Commits Offence As Principal Accused - Supreme Court

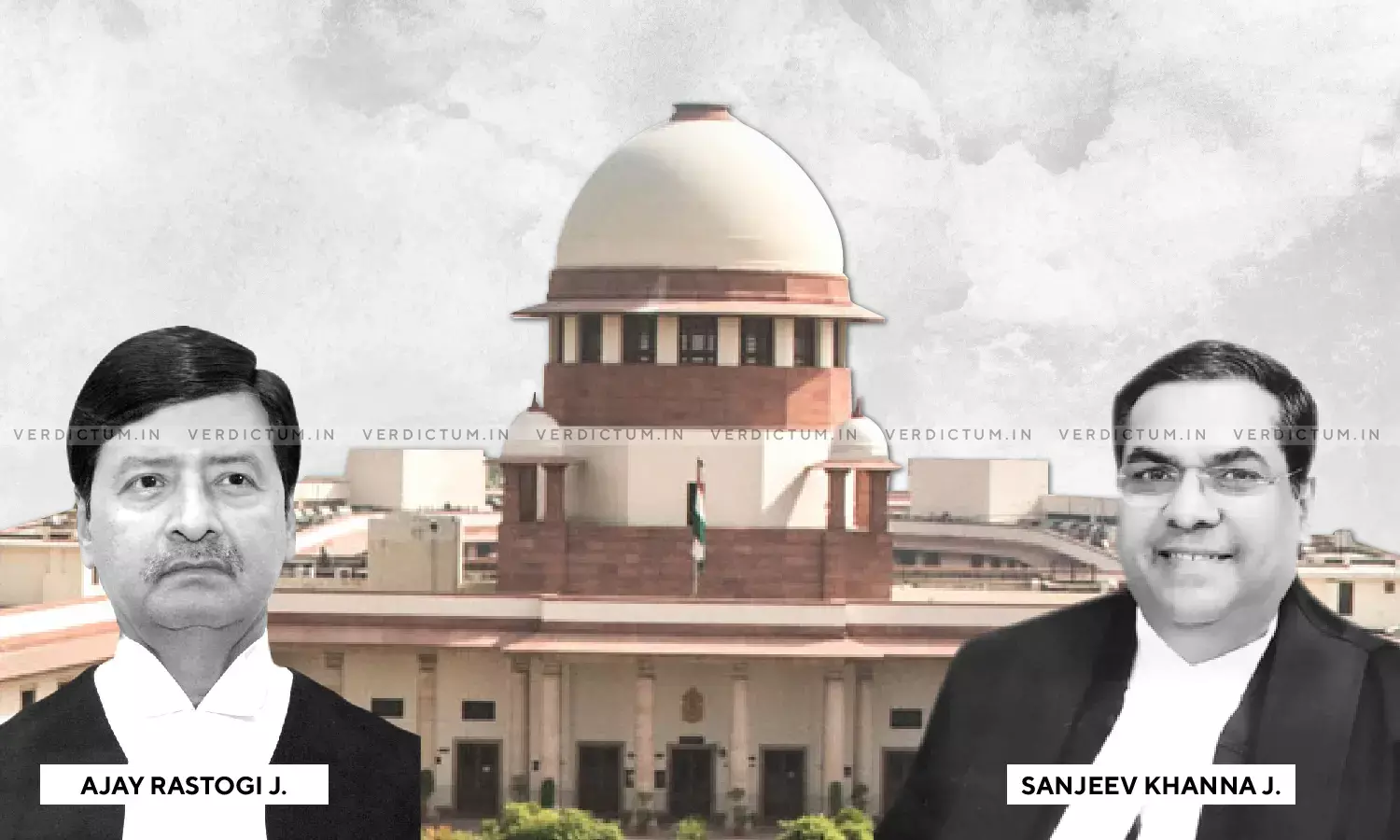

A Supreme Court Bench of Justice Ajay Rastogi and Justice Sanjiv Khanna set aside an order passed by the Chattisgarh High Court regarding conviction under the Negotiable Instruments Act on the aspects of vicarious liability of a partner.

The Court found that a partner in a firm cannot be convicted unless the firm has committed the offence as the principal accused. To that end, the Court opined that "The appellant cannot be convicted merely because he was a partner of the firm which had taken the loan or that he stood as a guarantor for such a loan."

The Respondent was a Bank who had granted term loans and cash credit facility to a Partnership Firm. The Firm issued cheques through its authorised signatory for part repayment of the loan. However, the cheques were dishonoured on presentation due to insufficient funds. Thereafter, the Bank issued a demand notice to the Firm under Section 138 of the Negotiable Instruments Act. The Bank also filed a complaint under the Section 138 of the NI Act before the Court of Judicial Magistrate against the Partners of the Firm, attempting to establish their vicarious liability. The Firm was not made an accused.

The Partners of the Firm were convicted by the Judicial Magistrate First Class under Section 138 of the NI Act, and were also asked to pay compensation under Section 357(3) of the CrPC. Their Appeal challenging their conviction was dismissed by the Sessions Judge, and the Appellate Court increased their sentence.

The Partners challenged the judgment before the High Court, which was dismissed with the observation that the liability under the NI Act is only upon the partners who are responsible for the firm for conduct of its business. One of the partners then approached the Supreme Court.

The Supreme Court noted that it had been admitted by the Bank that the Appellant had not issued the dishonoured cheques in his personal capacity or otherwise as a partner.

Relying on Girdhari Lal Gupta vs D.H. Mehta and Another, the Court opined that since the Respondent did not produce any evidence to show and establish that the Appellant was in charge of and responsible for the conduct of the affairs of the Firm, the conviction of the Appellant must be set aside.

To that end, the Court opined that "The Partnership Act, 1932 creates civil liability. Further, the guarantor's liability under the Indian Contract Act, 1872 is a civil liability. The appellant may have civil liability and may also be liable under the Recovery of Debts Due to Banks and Financial Institutions Act, 1993 and the Securitisation and Reconstruction of Financial Assets and Enforcement of Security Interest Act, 2002. However, vicarious liability in the criminal law in terms of Section 141 of the NI Act cannot be fastened because of the civil liability. Vicarious liability under sub-section (1) to Section 141 of the NI Act can be pinned when the person is in overall control of the day-to-day business of the company or firm. Vicarious liability under sub-section (2) to Section 141 of the NI Act can arise because of the director, manager, secretary, or other officer's personal conduct, functional or transactional role, notwithstanding that the person was not in overall control of the day-to-day business of the company when the offence was committed. Vicarious liability under sub-section (2) is attracted when the offence is committed with the consent, connivance, or is attributable to the neglect on the part of a director, manager, secretary, or other officer of the company."

The Court also opined that under the provisions of Section 141 of the NI Act, unless the Firm has committed the offence as a principle accused, the persons mentioned in sub-section (1) or (2) would not be liable or convicted as vicariously liable. To that end, the Court placed reliance on a catena of judgments including Sharad Kumar Sanghi v. Sangita Rane.

Accordingly, the Supreme Court set aside the order of the High Court and acquitted the Appellant.Click here to read/download the Judgment