Administrative Orders Must Be Read In Light Of Concomitant Record; Reasons Not Be Stated In Haec Verba: Supreme Court

The Supreme Court said that the legitimacy of administrative reasoning must be tested with reference to the material that existed at the time the decision was made, not by subsequent embellishment.

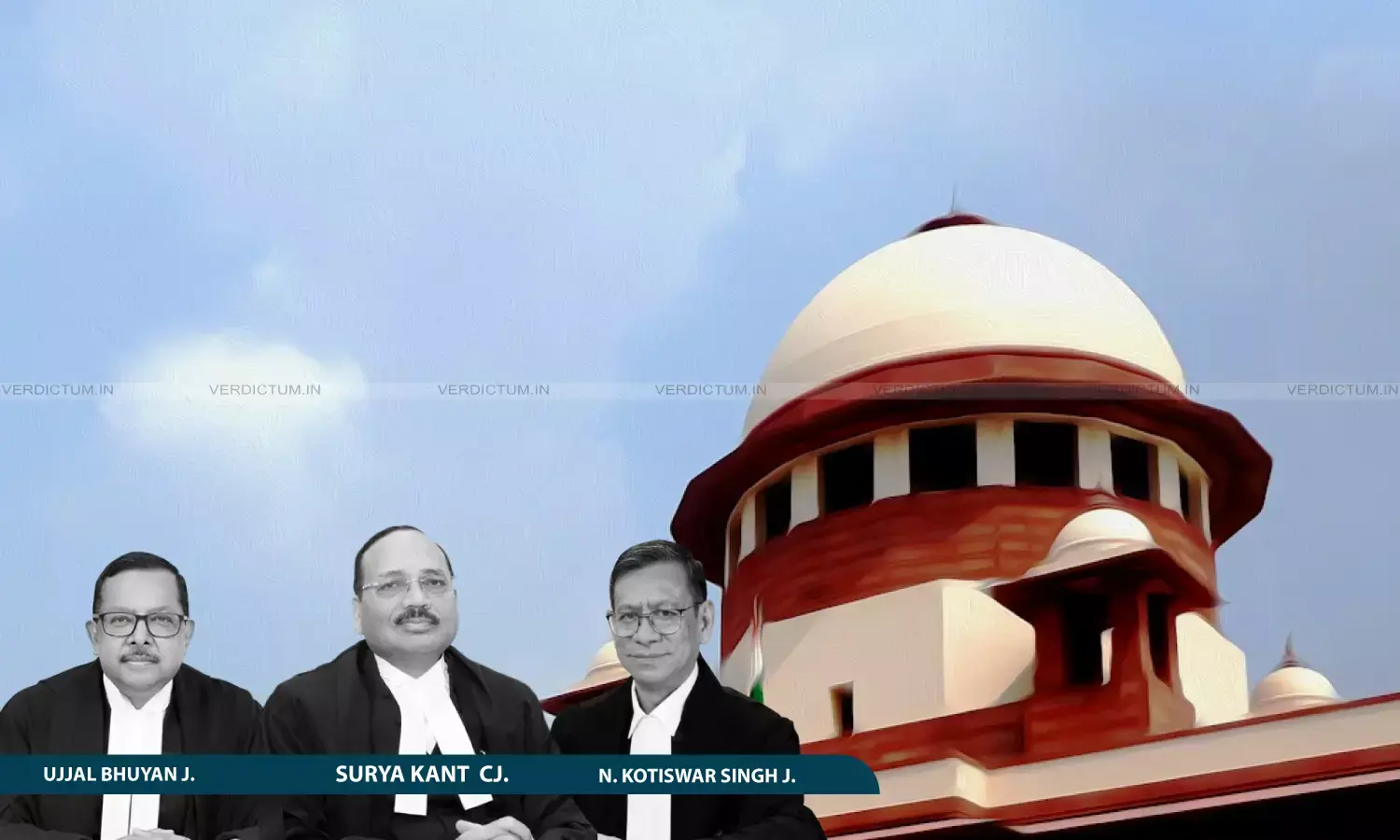

CJI Surya Kant, Justice Ujjal Bhuyan, Justice N. Kotiswar Singh, Supreme Court

The Supreme Court reiterated that the administrative orders must be read in light of the concomitant record, and the reasons need not be stated in haec verba in the communication.

The Court was deciding a Civil Appeal filed by the State of Himachal Pradesh in a case arising from a dispute concerning government tenders. The State challenged the Judgment of the High Court by which the cancellation of a Letter of Intent (LoI) was set aside.

The three-Judge Bench comprising Chief Justice of India (CJI) Surya Kant, Justice Ujjal Bhuyan, and Justice N. Kotiswar Singh observed, “Turning then to the factual record, the Cancellation Letter at first blush appears to be laconic; as it does not list the grounds that weighed upon the Department while issuing the same. … That being said, it is equally true that this Court has consistently held that administrative orders must be read in light of the concomitant record, and that reasons need not be stated in haec verba in the communication, so long as they can be discerned from the file and are not post-hoc justifications.”

The Bench said that the legitimacy of administrative reasoning must be tested with reference to the material that existed at the time the decision was made, not by subsequent embellishment.

“To simplify: what is permissible is elucidation of contemporaneous reasoning already traceable on record; what is impermissible is the invention of fresh grounds to retrospectively justify an otherwise unreasoned order”, it added.

Senior Advocate P. Chidambaram appeared for the Appellants, while Senior Advocate Sanjeev Bhushan appeared for the Respondent.

Facts of the Case

The dispute emanated from the endeavour of the Appellant-State to modernise the functioning of its Public Distribution System (PDS). To that end, in 2017, the State’s Department of Food, Civil Supplies and Consumer Affairs had engaged the Respondent-company for the supply and maintenance of ePoS devices at Fair Price Shops across the State. The said arrangement, being a rental model, continued in operation for several years and formed the technological base for the State’s PDS till its expiry. In the financial year 2021-22, the State Government resolved to upgrade this ostensibly obsolete system by introducing enhanced ePoS devices equipped with biometric and IRIS-scanning facilities, making them inter alia capable of integration with electronic weighing scales. The reform was intended to allow an Aadhaar-enabled Public Distribution System (AePDS) to ensure transparency and better service to the beneficiaries. Subsequently, the Department invited an Expression of Interest from eligible manufacturers and system integrators to supply and maintain such upgraded devices.

Several agencies participated in that process, one of which was the Respondent company itself. However, none of the bidders including the Respondent qualified for the same. Ultimately, Letter of Intent (LoI) was issued to the Respondent. One of the unsuccessful bidders addressed a complaint to the Department alleging that the Respondent had suppressed material facts which would render it unfit for participation in the tendering process. Thereafter, a Cancellation Letter was sent to the Respondent by the Department. Being aggrieved, the Respondent submitted a representation to the Department seeking withdrawal of the cancellation letter. However, the same was not accepted and hence, it approached the High Court. The High Court issued a notice and permitted the State to proceed with the fresh tendering, but directed that no final decision be taken without its leave. As the Writ Petition was allowed, the case was before the Apex Court.

Court’s Observations

The Supreme Court in the above context of the case, noted, “… the LoI was no more than a provisional communication signifying the Appellant-State’s intent to enter into a formal arrangement upon fulfilment of certain technical and procedural conditions. The acceptance of tender and the consequential formation of a binding contract were contingent upon satisfaction of these prerequisites. The Respondent-company’s reliance upon the LoI as a source of vested contractual rights is, therefore, wholly misplaced.”

The Court was of the view that the LoI did not give rise to any binding or enforceable rights in favour of the Respondent company and that even when contractual rights are absent, the State’s administrative discretion in rescinding or cancelling an LoI is not unfettered.

“It remains subject to constitutional discipline, particularly the requirement that State action must not be arbitrary, unreasonable, or actuated by mala fides”, it added.

The Court reiterated that judicial review in contract matters operates only where the action is “palpably unreasonable or absolutely irrational and bereft of any principle”.

“These principles are neither ornamental nor abstract. They arise from the nuanced understanding that government contracting, unlike private commerce, is an instrument of governance. The Rule of Law demands that Executive discretion be rational and fair, but it equally demands that Courts respect the autonomy necessary for effective administration. Public interest requires not judicial micro-management but judicial assurance that power has been exercised within lawful bounds”, it emphasised.

The Court remarked that the State, as a continuing juristic entity, is bound by its own representations in prior proceedings; its legal stance cannot oscillate with changes in political leadership.

“The blacklisting complaint, by itself, could not constitute a valid basis for rescinding the LoI, and its invocation betrays a want of administrative consistency and adherence to due process”, it said.

The Court observed that the performance in anticipation cannot metamorphose into a legal right where the parties themselves have prescribed a structured order of steps.

“In arriving at its contrary view, the High Court appears to have proceeded on an erroneous conflation of ‘taking steps’ with ‘taking the right steps’. … Compliance in law must be with the document that governs the relationship, not with the bidder’s self-chosen course of conduct. To equate unilateral readiness with contractual fulfilment is to disregard the essential discipline of tender law, which binds both sides to the terms they themselves framed”, it further said.

The Court enunciated that where a bidder has agreed that testing, demonstration, and cost disclosure are preconditions to finalisation, it cannot later assert that the LoI was already complete, notwithstanding the absence of those acts.

“Administrative deliberation does not amount to duplicity. It is entirely natural that a department exploring compliance would keep lines of communication open while simultaneously assessing whether continuation was tenable. The law does not demand that the State speak only after it has made up its mind; it demands only that its final decision be traceable to reason, not to whim. The record before us meets that threshold”, it also noted.

The Court clarified that where the effect of administrative action is to enhance openness and restore competition, Courts are doubly cautious before imputing mala fides.

“Lapse of time does not convert a provisional arrangement into a vested right. The expectation that the Government will ultimately formalise an LoI may be legitimate in the commercial sense, but it is not enforceable in law unless the conditions for formal acceptance are met. The constitutional guarantee against arbitrariness is not a charter of commercial expectations; it is a safeguard against irrationality, and none is established in this record”, it added.

Furthermore, the Court reiterated that the State’s decision to cancel a tender or restart the process is itself an aspect of public interest. It said that to invoke legitimate expectation against an explicit disclaimer would be to transform the doctrine from a shield against arbitrariness into a sword against caution — a proposition no Court can endorse.

“The cancellation of the LoI dated 02.09.2022 does not suffer from arbitrariness, mala fides, or breach of natural justice, and the High Court’s interference therewith cannot be sustained. The Department had tangible grounds for dissatisfaction; it followed a discernible process; and it acted within the contractual liberty reserved to it. The reasons for cancellation were antecedent, bona fide, and germane to the public purpose of ensuring a reliable, uniform, and lawfully procured ePoS infrastructure”, it held.

Conclusion

The Court took note of the fact that the tender in question was not a commercial exercise in isolation but an instrument of social welfare, intended to secure efficient and transparent delivery of subsidised foodgrains to the most vulnerable citizens.

“The Public Distribution System remains, for millions, the thin line between sustenance and deprivation. When projects of such public importance are delayed or derailed by procedural lapses, the ultimate cost is borne not by the contracting parties but by those at the last mile of governance”, it elucidated.

The Court emphasised that it is incumbent upon every stakeholder—the Government, its technical partners, and private participants—to treat such undertakings with the seriousness their human impact demands.

“Administrative caution and technological innovation must work hand in hand to ensure that reform does not lose sight of its moral anchor: service to the poorest. Future exercises in public procurement, particularly those that underpin welfare delivery, must thus be executed with greater institutional coherence, foresight, and accountability—so that legality, efficiency, and compassion operate in concert, and the constitutional promise of equitable distribution finds tangible expression”, it concluded.

Accordingly, the Apex Court allowed the Appeal, set aside the impugned Judgment, and directed the State to hold a Fact-Finding Enquiry in association with the Respondent company.

Cause Title- State of Himachal Pradesh & Anr. v. M/s OASYS Cybernatics Pvt. Ltd. (Neutral Citation: 2025 INSC 1355)