Dedication Of Property For Religious Purposes Does Not Require Express Dedication Or Document - SC

Dedication Of Property For Religious Purposes Does Not Require Express Dedication Or Document - SC

The Supreme Court while restraining the Appellant from interfering in any manner with the right of the Temple authorities to take out the suit jewellery from the Kudavarai whenever the occasion demands has held, "The dedication of the suit jewellery does not require an express dedication or document, and can be inferred from the circumstances, especially the uninterrupted and long possession of the suit jewellery by the respondent/Temple."

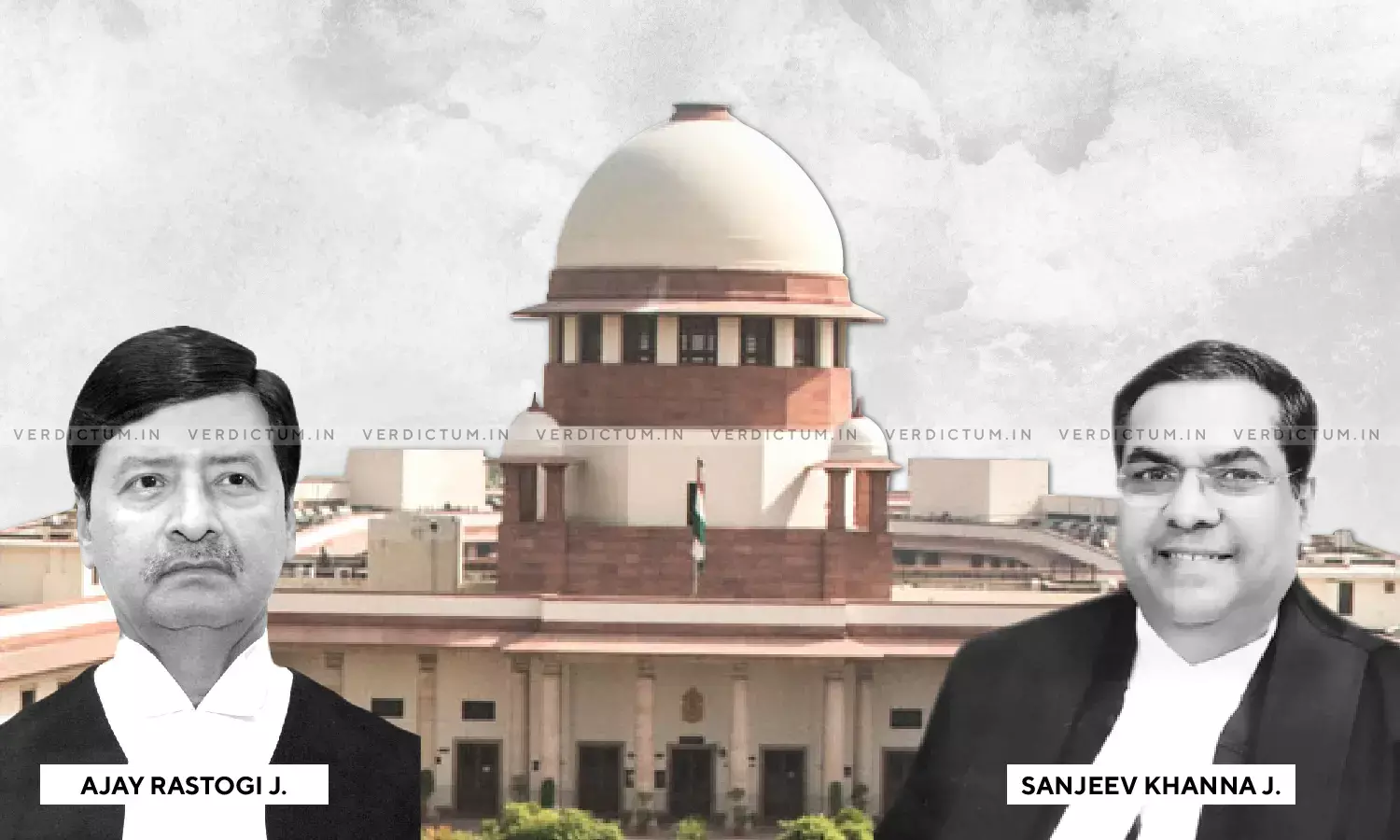

A two-judge Bench of Justice Ajay Rastogi and Justice Sanjiv Khanna also held that "Extinction of private character of a property can be inferred from the circumstances and facts on record, including sufficient length of time, which shows user permitted for religious or public purposes."

Counsel V.N. Raghupathy appeared for the Appellant while Counsel Vinodh Kanna B. appeared for the Respondents before the Apex Court.

In this case, the Appellant filed a suit claiming that jewellery was inherited by him as his personal property, being the adopted son of a married couple. He also sought a mandatory injunction to the Temple to permit him to maintain independent and exclusive possession and enjoyment of the Kudavarai of the Temple.

The Temple objected to the suit, stating that the Appellant did not hold title over the jewellery, and the custody over the keys of the Kuduvarai by his father was merely an honorary responsibility.

The Temple also stated that the jewellery was donated by the ancestors of the father, absolutely to the deity and therefore was a specific endowment attached to the Temple.

The suit was dismissed by the Trial Court, mainly on the ground that the suit was not maintainable as per the provisions of Section 109 of the Tamil Nadu Hindu Religious and Charitable Endowments Act, 1959. This judgment was upheld by the First Appellate Court and the High Court.

The Supreme Court referred to a catena of judgments including M.R. Goda Rao Sahib v. State of Madras and the provisions of the Act, to opine that "In the context of the present case and the facts recorded above, it is clear that the suit jewellery was a 'specific endowment' for the performance of the specific service of adorning the deity, Sri Neelayadhakshi Amman, to be taken out in the Temple car and ratham in a grand procession during the Adipooram festival. Further, as explained below, it was a charity in favour of the Temple and was for performance of a religious charity. The involvement of the family of the appellant was limited and restricted to retaining the keys of the Kudavarai and the iron safe which were to be opened at the time of the festival of Adipooram and the suit jewellery was to be taken out for the specific purpose of adorning the deity, Sri Neelayadhakshi Amman."

Opining that the Appellant's case did not have any statutory or legal backing, the Court said "Therefore, in view of the judgments quoted above and the aforesaid statutory provisions, it must be held that the case of the appellant that there was no endowment or specific endowment must fail and has no legs to stand on. The dedication of the suit jewellery does not require an express dedication or document, and can be inferred from the circumstances, especially the uninterrupted and long possession of the suit jewellery by the respondent/Temple. The private character of the jewels had extinguished long back and the appellant has no basis to claim that the suit jewellery was inherited by him from his adoptive parents. The endowment is clearly public in nature and for the purposes of performing religious ceremonies. As confirmed by three courts, with which we are in agreement, the suit jewellery was dedicated for a specific purpose and can only be used during the performance of the religious ceremony during the Adipooram festival."

The Apex Court also passed a decree ordering the Appellant to cooperate with the requests made by the Temple to open the Kudavarai doors and take out the jewellery from the iron-safe whenever required.

Click here to read/download the Judgment