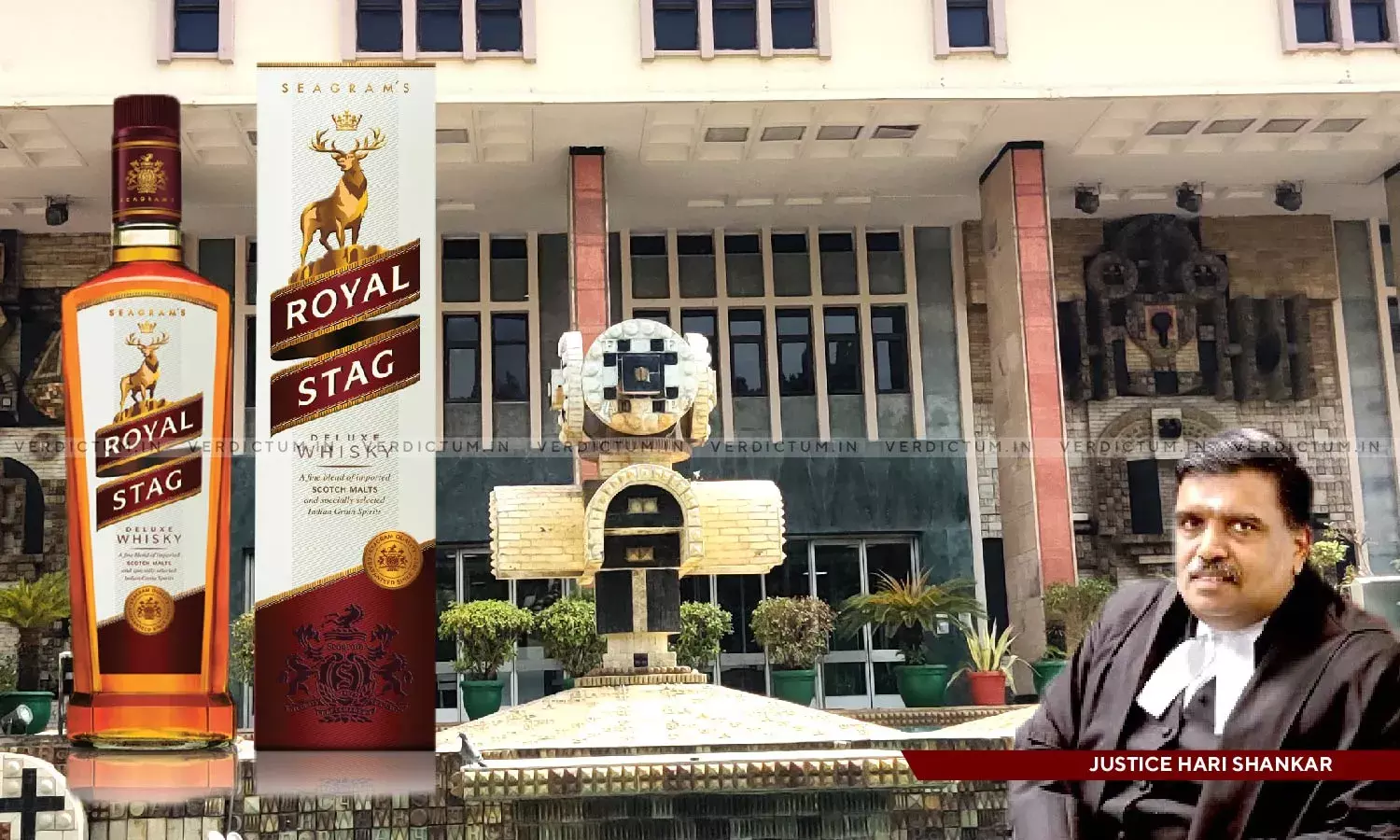

Royal Stag Trademark Infringement Suit- Delhi HC Confirms 2019 Order Restraining Two Manufacturers From Dealing In Alcoholic Beverages Under Mark "Indian Stag"

A Delhi High Court Bench of Justice C Hari Shankar has confirmed a 2019 interim order which restrained two sellers from dealing in liquor and alcoholic beverages under the mark "Indian Stag". This came after a trademark infringement suit was filed by Indian whiskey brand "Royal Stag".

In that context, it was said that, "a prima facie case of infringement, by the use of the INDIAN STAG marked by the defendants, of the plaintiff’s ROYAL STAG mark, for IMFL, is made out, warranting interim injunction as sought".

Counsel Hemant Singh and Counsel Mamta Rani Jha, among others, appeared for the plaintiff, while Counsel Rajeshwari and Counsel Swapnil Gaur appeared for the defendant.

In this case, the plaintiff had ownership of trademarks related to alcoholic beverages, with a primary focus on the "ROYAL STAG" brand. They argued that these trademarks, particularly "ROYAL STAG" and a Stag device, had become widely recognized and associated with their products.

The defendant had been producing and exporting their own Indian Made Foreign Liquor (IMFL) under the "INDIAN STAG" brand. The plaintiff claimed that the defendant's "INDIAN STAG" brand, including the Stag device and the word "Stag," was deceptively similar to their trademarks, constituting trademark infringement under the Trade Marks Act, 1999.

The defendant argued that "Stag" was a common term in the liquor industry and could not be exclusively claimed by the plaintiff. They argued that their brand was visually and phonetically distinct and catered to a different market.

While the Court granted interim relief, the matter was analysed on several parameters.

Deceptive Similarity

The Court observed that once the essential features of the plaintiff's mark are replicated in the defendant's mark, infringement within the meaning of Section 24(2)(b) of the Trade Marks Act, has necessarily to be found to have taken place. In light of the same, the Court observed that, "All criteria envisaged by the provision are met. The marks are similar; they are used for the same product, and, owing to these factors, there is a likelihood of confusion, or at the least association, in the mind of a consumer of average intelligence and imperfect recollection."

Subsequently, it was held that on a plain comparison between the plaintiff's and defendants' marks, the defendant had infringed the plaintiff's mark.

The plea of disclaimer

It was observed that there was no embargo on the plaintiff claiming exclusivity in respect of the STAG part of its mark. Further, it was observed that the marks were deceptively similar because the defendant replicated the STAG part of the plaintiff's mark, and therefore, when the two marks are seen as whole marks, especially in conjunction with the stag motif, and the fact that both the marks are used for IMFL, there was a clear possibility of likelihood of confusion.

In light of the same, it was held that, "The disclaimer entered in respect of ROYAL part of the plaintiff’s mark, while granting registration to the plaintiff’s ROYAL STAG mark cannot, therefore, make any difference."

Section 17 of the Trade Marks Act

The Court observed that if Section 17 of the Act were to be applied to the case, "the plaintiff cannot claim exclusivity either in respect of the ROYAL or in respect of the STAG part of its mark, as neither part is separately registered as a trade mark and, additionally, the ROYAL part of the plaintiff’s mark stands disclaimed. Nothing, however, prevents the plaintiff from predicating its case of infringement on deceptive similarity between ROYAL STAG and INDIAN STAG seen as whole marks."

In light of the same, the Court reiterated that such similarity did exist.

Likelihood of confusion

It was observed that the possibility of likelihood of an association between the two marks, in the minds of a consumer of average intelligence and imperfect recollection, could not be ruled out. In that context, it was also said that, "a consumer of average intelligence and imperfect recollection, who has come across the plaintiff’s mark at one point of time and chances on the defendants’ mark later – and does not see them side by side – is likely to be in a state of wonderment as to whether he has seen the same mark, or an associated mark, earlier. If, proverbial hand on proverbial chin, he is even inclined to reflect on the point, that suffices to constitute infringement".

Relevance of Section 56

Section 56 of the Act deems application of a trade mark to goods which are to be exported, to be deemed to constitute use of the said mark in respect of the goods, for any purpose for which such use is material under the Trade Marks Act, as if the mark was being applied to goods which were to be traded within India.

With that background, it was observed that, "The use of the rival marks in India is undoubtedly relevant for the purposes of Section 29(2)(b) of the Trade Marks Act. “Likelihood of confusion”, within the meaning of the said provision, would, therefore, have to be examined by deeming the goods, on which the defendants affixes its INDIAN STAG mark, to be traded within India, extrapolating the deeming fiction engrafted by Section 56 to its logical end. One has to examine the likelihood of confusion on the deeming premise that a consumer of average intelligence and imperfect recollection comes across, within India, the marks of the plaintiff and the defendants, even if, in actual fact, he does not."

"STAG" being publici juris and common to the trade

The Court observed that the word "STAG" is ineligible for registration as a trademark, which makes it not public juris. It was further observed that the contention that STAG is common to the whiskey trade was also of no consequence, as the plaintiff's mark was not "STAG" but "ROYAL STAG".

Infringement of the Stag device

The Court observed that, "Plainly, there is no visual similarity between the two stags. The registration, in favour of the plaintiff, of a device mark representing a stag, cannot confer a monopoly, on the plaintiff, of any and every stag device. The competing marks being device marks, with no textual component, a visual comparison has necessarily to guide any decision on infringement. On a visual comparison, the two stags cannot be said to be alike, or even similar."

Therefore, it was held that the defendants' stag device did not infringe the plaintiff's.

Use of Scottish Stag by IMUK

The Court noted that trade marks are territorial, and the same would apply to the Scottish Stag mark. In that context, it was said that, "The extent of user of the SCOTTISH STAG mark, by IMUK, outside the territory of India, cannot dilute the effect of infringement of the plaintiff’s ROYAL STAG mark by the use, by the defendants, of the INDIAN STAG mark, as the use, in both cases, is in India. Th territorial rights to protect its registered trade mark from infringement, which Section 28(1) of the Trade Marks Act guarantees to the plaintiff cannot, therefore, be defeated by the use, howsoever extensive, of the mark SCOTTISH STAG by IMUK – even assuming it to be interconnected with Defendant 2 – outside the territory of India."

Acquiescence

The Court held that beyond a bald plea that the defendants’ INDIAN STAG and the plaintiff’s ROYAL STAG were sold together at various outlets in Dubai, there was no substantial evidence to indicate awareness, by the plaintiff, of the use, by the defendants, of the impugned INDIAN STAG mark, much less of acquiescence to such use for a continuous period of five years or more.

In light of the same, it was said that, "The conditions of Section 33 are not satisfied. Ergo, the plea of acquiescence has necessarily to fail."

Passing Off

The Court observed that given the difference in the visual appearance of the defendants' and plaintiff's labels, and the fact that the defendants' product was entirely exported, any finding of passing off would require the Court to be satisfied that, in foreign markets, consumers might mistake the defendants’ goods for the plaintiffs.

In light of the same, it was said that, "I am unable to arrive even at the prima facie finding in that regard on the basis of the material on record. At the very least, this issue would require leading of evidence and trial."

Cause Title: Pernod Ricard India Private Ltd. vs AB Sugars Ltd. & Anr.

Click here to read/download the Judgment